People often ask what being an archivist actually means. In truth, the role is so varied that it’s almost impossible to define an average ‘day in the life’ for any archivist, although like most professions these days, at least some of it will be spent in front of a screen answering emails!

Whatever their archive is comprised of and wherever it’s located, archivists will always acknowledge that their primary duty is to the unique and invaluable records in their care – records that that we preserve and make available for researchers now and in the future. Practical measures to achieve this goal are as relevant as ever, and one activity in particular is something that most archivists are very familiar with: cleaning.

Archival material can be dirty. Very dirty. Whether it be the result of poor environmental conditions or the way records have been stored over the centuries, the dust of the ages is real and – without exaggeration – an existential threat to historic documents. This is why archivists undertake gentle surface cleaning of items in their collections, leaving more serious problems like rips, tears and holes to professional conservators.

What does surface cleaning achieve? In the first instance, removing dirt and dust from archive material instantly improves aesthetics and can have a surprising effect on the legibility of information beneath the grime. Dirt is also hygroscopic, meaning that it absorbs moisture and pollutants – so removing as much as possible is essential for preservation purposes. Moreover, dirt is attractive to mould and pests like insects (not welcome visitors to an archive), giving an additional and very compelling incentive for its removal. Finally, clean documents are simply more pleasant to handle, for researchers and archivists alike.

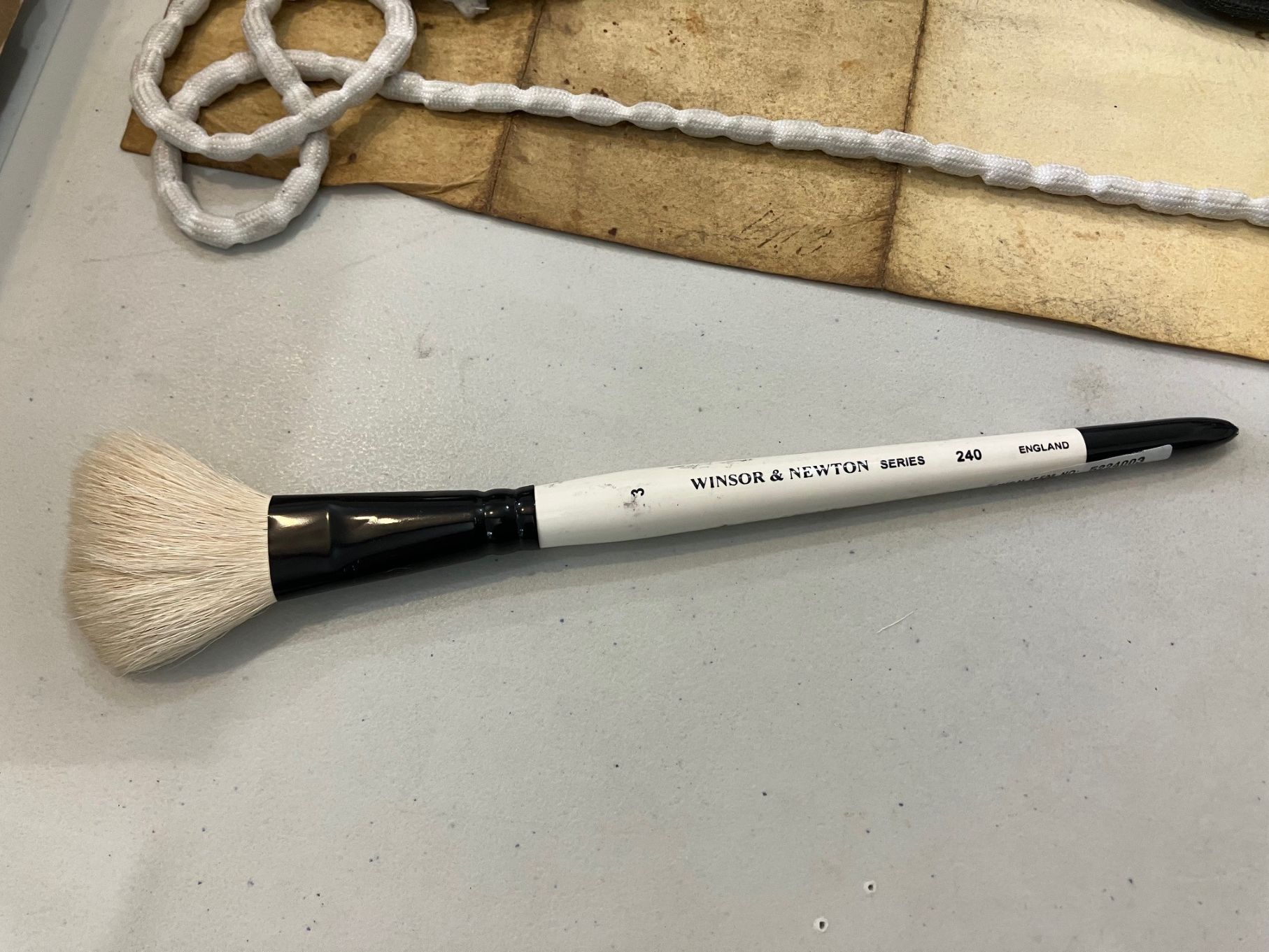

So, what does the surface cleaning process look like? Two methods are typically used, both with pros and cons. The soft brush method is often a starting point for most cleaning activities, and the only realistic option for the most fragile documents. Here a conservation grade brush (usually made from goat hair) is used to gently brush an item from the centre outwards. It’s quick at removing dust from large areas and has little impact on the surface of a paper or parchment document. On the other hand, it cannot remove ingrained dirt, and there is a slight risk of abrasion from particles moving over the surface.

The latex smoke sponge is a step up in terms of cleaning power. Here small squares of sponge are used to gently dab at the surface of an item, removing ingrained dirt and capturing it in the substrate of the sponge. When all the sponge’s surfaces are dirty, it can simply be cut with scissors to reveal a fresh layer underneath for renewed cleaning. The downside of this method, however, is that residual pieces of sponge can be left behind, and there is always the risk that the increased friction can catch on tears or roughen paper fibers. Smoke sponge users must also take care not to erase the very information they seek to reveal, avoiding especially any text written in pencil!

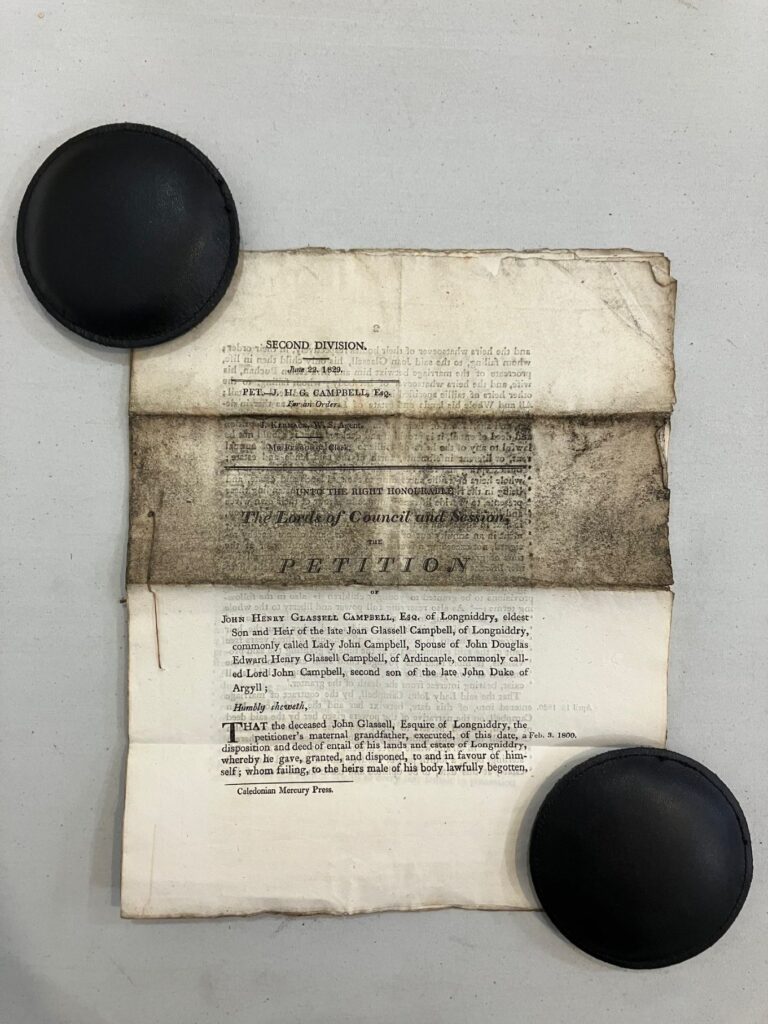

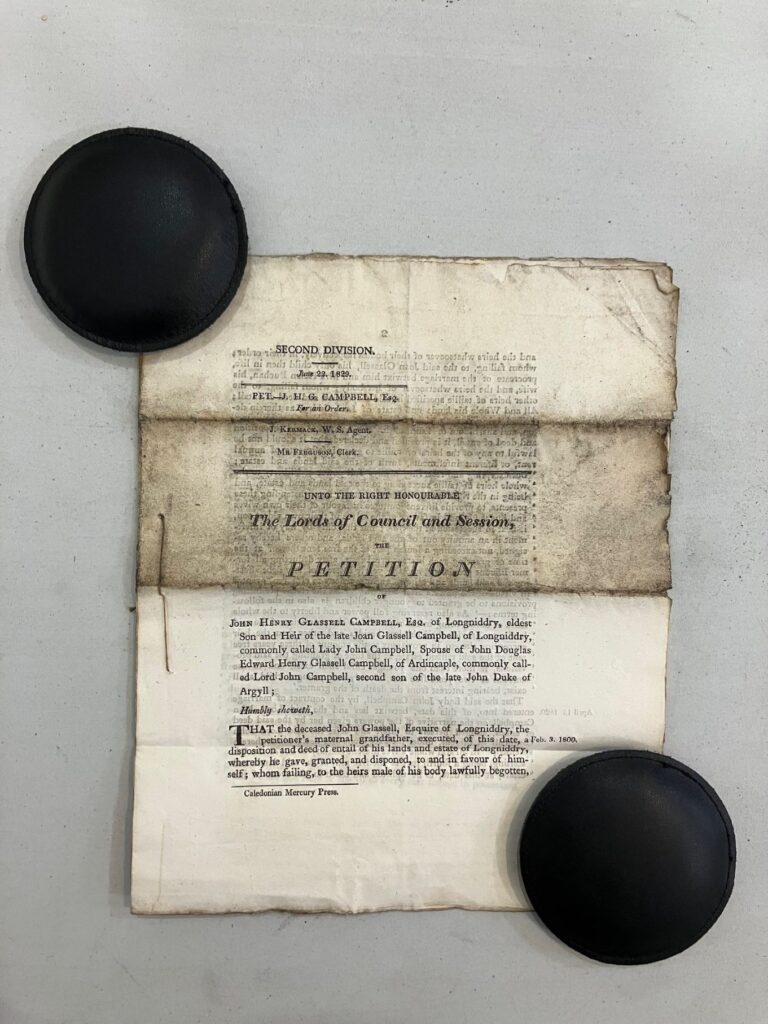

Take a look at these before and after shots of a recently cleaned document from the archive. It’s a printed copy of an 1829 petition to the Court of Session on behalf of John Henry Glassell Campbell of Longniddry (1821-1837), eldest son of Lord John Campbell, later 7th duke of Argyll, and his second wife Joan Glassell. The petition sought to clarify in law the amount of annuity payable to Lord John following Joan’s death in 1828. This measure was apparently needed because the two annuities originally granted by Joan to her husband were more generous than the rental income of the Longniddry estate could support.

One image shows the petition’s title page before cleaning with a smoke sponge, and the other after cleaning has taken place. The difference in legibility can clearly be seen – and the extent of the dirt removed is shown very starkly in the image comparing the sponge used to do the cleaning with an unused one! Those handling the petition in future will also avoid getting grubby hands and, potentially, transferring that dirt to other items in the archive.

Occasionally we bring groups of volunteers together to tackle surface cleaning on a larger scale. Previous sessions have involved spending a day cleaning and repackaging items from our extensive (and very beautiful) maps and plans series. Friends of Argyll Estates Archives get first refusal on all these volunteering opportunities, so keep an eye out on this website or the Friends Facebook page if you would like to help us clean up our act!